-

The cost of a full sales assisted stock order vs. an e-commerce unassisted

order is $50 to $100.

-

The immediacy of price and availability on the Internet has, for many items,

suppressed the ability to fetch a higher price.

-

Global manufacturing has reduced cost appreciation on many products and, in

some instances, there has been cost deflation.

-

Modern day cost-to-serve models are becoming more commonplace and the consensus

is that 40% of customers, sales territories, segments, transactions and

marketing programs have returns above the hurdle rate, 20% have positive

returns that are below the hurdle rate and 40% have negative returns.

-

New models of distribution are appearing that offer price advantages over the

bundled model of 10% to 30%.

- Customers are value-driven as long-term forecasts for the economy are at “stall speed” of 2% GDP or less.

Signs and Stresses of Bundle-Crumble

Since 40% of investments cover the remaining 60% of poor or negative investments, distribution is a “bundled” model where the phenomenal profits of the top 40% of customers, transaction types, sellers, vendors, etc., cover everything else. In short, distributors deploy a type of Robin-Hood strategy where thewealthy and healthy minoritycovers the less fortunatemajority.As wholesalers become savvier on service costs, some develop low-cost offerings and go after their competitor’s top investments. New or local market entrants develop Transactional Models and their strategy is based on taking the most lucrative customers from the competition with a low service cost model.[1] They often grow rapidly and become a market force in five to 10 years. The result is that the bundled service model begins a slow crumble, or “Bundle-Crumble.”

As the most lucrative customers are lured away by low-cost entrants, the bundled wholesaler is left to raise prices and reduce services on remaining lucrative customers. Of course this exacerbates the situation and existing customers begin to leave the incumbent supplier. There has been an increased appearance of Transactional Wholesalers, Global Importers and spin-offs of traditional distributors that offer a lower cost service and best cost product that will, based on our research, facilitate a slow decline of the traditional one-size-fits-all model.

Low-cost entrants unbundle (disintermediate) the traditional gazillion products/full-service model, but today many wholesalers don’t face transactional competition. We expect this to change as transactional strategies are growing in many of the 50 B2B vertical markets served by distributors. As for PCHP wholesalers, we expect the transactional model to be used in numerous ways including:

- More

direct shipments by importers to end customers; especially for extra large

orders;

- Truncated

product offerings of A and some B products to customer bases that can hold

inventory (think Industrial/Institutional MRO and Residential HVAC); and

- Alignment of the transactional model with large customers who place large stock orders and targeting the competition’s top customers.

Transactional strategies, in the long run, bring cost(s) down for end users and make the channel more competitive. For the unprepared, however, they can be business altering. Too, with the advance of e-commerce buying and communication via e-mail, many distributors find information asymmetries, which have allowed for price premiums in the past, no longer exist. We find where, for most distributors, product price and availability is found online and easily accessible 7/24.

Additionally, the preference for Generation X and Y buyers is to receive quotes through e-mail via the mechanism known as auction pricing. Ergo, when quality of information is profuse and the business environment is slow growth and less forgiving, cost control and careful planning of the product and service offering(s) are key.

In summation, we forecast a low-cost and more competitive channel driven by the confluence of cost-to-serve knowledge, transactional models and pervasiveness of price and availability. A certain amount of bundle-crumble is to be expected as these changes transpire. This rate of crumble is accelerated by another common wholesaler behavior called Branchitis.

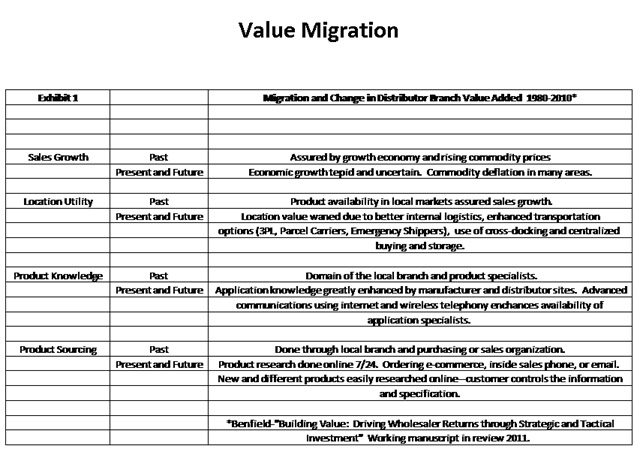

Exhibit 1. (See the pdf below for a larger view.)

Branchitis-A “Genetic” Disorder

The focus on the Wholesaler Branch to drive financial performance is legendary. The branch is, in most wholesale firms, far more than a logistics entity. Branches are profit and loss centers with goals and measures spanning operations, sales, finance, asset management, marketing and customer satisfaction. In essence, the branch is a business unit and the Branch Manager is a key position in driving performance. We call the focus on the branch “Branchitis” and define it as a “genetic” disorder formed around market needs of a bygone era and passed down three and four generations.As wholesaling has consolidated, firms become larger, and the work becomes more complex. Hence, we have argued that many branch functions will become strategically controlled at the home office. For instance, the pricing function, often controlled at the branch has, in the last decade, moved a large part of its nerve center to the home office. Modern pricing practices of segmentation, transaction-based pricing, pricing waterfall analysis and using cost-to-serve measures in price decision-making are complex and require specialization of knowledge and resource planning with IT.

The change in pricing is mirrored in many other disciplines including sales management, business development, accounting, purchasing and operations. We increasingly believe that wholesalers will develop functional specialists in lieu of having the functions, like pricing, defined by the branch manager. We also expect a significant amount of strategic direction and decision-making for the discipline(s) to be done at corporate. Because of these changes, we will find less control of these functions by branch managers and, today, find where a growing number of wholesalers have supplanted the position with a regional manager who controls several branches. Our experience and forecast, however, are often opposite the experience of many wholesalers who grew up in the business and base their value propositions around the local branch and branch manager.

Today, many elements of the local branch’s value proposition have been rendered less effective as a differentiating factor. The “value” list is captured below inExhibit 1[2] (see below for pdf) and is under the subject of Value Migration. Value perceptions by the customer and value offerings by the distributor change over time. In general, service value becomes less costly and higher in quality. The change is due to advances in logistics technology, knowledge of handling cost and better forecasting. In most instances, service value is the primary value added by the distributor including product knowledge and developing relationships with professional users.

Exhibit 1 depicts the change in the major elements of service value over a 30-year period (1980-2010). For instance, sales growth was once assured by a growth economy and rising commodity prices. Today, however, the economic growth is at stall speed and many products are coming down in price. Hence, the value proposition for sales growth has migrated as globalization of manufacturing has created an environment where many prices are stagnant or deflating.

Another value-added service is place or location utility. In the past, the more brick and mortar locations that were available, the better financial performance. Today, however, reduced delivery cost from routing software, enhanced transportation and storage options, better usage forecasting and advances in material handling have reduced the need for brick and mortar locations. Today, branches often serve shipping radii, with a variety of carriers and storage options that were unheard of a generation ago. In essence, the value of branch location hasmigratedand this is primarily due to technology and advancement in knowledge of logistics and handling costs. Today, given the 7/24 of pricing and availability and reduction in information asymmetries because of the Internet, too many brick and mortar locations can become a liability.

In contrast to value migration, many wholesaling executives’ formal experience was gained decades ago when technology was limited, communication and ordering were done via phone or sales call and product expertise was available through branch personnel. Hence, a real impediment to streamlining the number of brick and mortar outlets is the predisposition of management whose formative experience was a generation ago. Our argument is that today’s cost competitive environment with 7/24 information, product deflation, detailed transaction costs and lower cost logistical options for material movement and storage will render numerous branch locations and their managers too costly and make the parent firm uncompetitive.

To our point, a recent announcement by Grainger regarded the closing of 25 branches after the company missed a quarterly forecast.[3]The trend in hard goods retailing is to close brick and mortar locations and this is primarily caused by e-commerce and the increasing desire of customers to purchase online.[4]For instance, there have been “scant” new book stores built since 1998 and some 40% of retail hard-goods are sold via the internet.[5]

We expect, as e-commerce is accepted by professional users in durable goods markets, a similar effect will be seen in wholesaler brick and mortar locations. Branchitis will be cured by advancement in logistics technology, detailed transaction costs and e-commerce. This change is already underway despite the experience of many wholesaler executives.

Anticipating Change and Doing Something About It

Our advice for wholesalers is to carefully consider the competitive pressures in today’s environment. Pervasiveness of price and availability via the internet, preferential use of e-commerce and auction pricing using email, detailed costs of transactions in cost-to-serve models, and lower cost logistics and material handling have combined to change distribution in a big way.Wholesalers who assume the predominant practices of bundling losing customers with profitable customers and having an operating platform chock full of branch managers with their own brick and mortar locations may be adding too much cost to a thin margin business. We fully expect bundle-crumble and branchitis to become increasingly debilitating problems for wholesalers who refuse to accept new technology and knowledge.

1 The recent bankruptcy at AMR (American Airlines) was in large measure the result of low-cost airline strategies by carriers like Southwest who, years before, eschewed the high cost /low return routes and targeted the most lucrative routes.

2 Excerpted from Building Value: Driving Wholesaler Returns through Strategic and Tactical Investment.” 2011

3 See announcement for branch closures of WW Grainger at: http://finance.yahoo.com/news/grainger-4q-estimate-falls-short-232043255.html

4 Favaro, K., Hodson, N. “The End of History or Retail 3.0” Harvard Business Review Blog, November 21, 2011

5 Ibid

Recent Comments

AliPromoCodes

[No title]

Considering the fact that a lot of firms...

Thanks for the comment, Dinni!...

All I know is that companies need to...