The concept of future success molded by today's decisions is inherent in the newest report, "Facing the Forces of Change: Four Trends Reshaping Wholesale Distribution," issued by the National Association of Wholesaler-Distributor's Distribution Research and Education Foundation and Arthur Andersen. The report is the fourth in a series on the state of wholesale distribution.

The 163-page report discusses four trends that will affect the distribution industry well into the 21st century: electronic commerce, strategic alliances, supply-chain integration and globalization.

"While it may be tempting to treat these four trends as separate issues, they're all interrelated," says Rick Prohammer, assistant wholesale distribution director at Arthur Andersen and a co-manager of the DREF project. "Electronic commerce is the locomotive pushing everything else forward."

The report notes that, over the last decade, the wholesale-distribution industry has dealt with numerous changes including overcapacity resulting in consolidation, shifts in channel power from manufacturers and wholesalers to customers, increasingly complex value-added customer demands resulting in customized approaches, and competition from such avenues as warehouse clubs and home centers. The next decade doesn't indicate any slowing down of these factors; in fact, they will probably accelerate.

As in the previous three DREF reports, this study tracks a trio of additional long-term tendencies that continue to affect the industry: manufacturers' use of multiple channels of distribution, wholesaler consolidation and company growth outpacing industry growth. While these issues pose a serious threat to the wholesaler, the four trends outlined in the DREF report present opportunities to change the perception of the wholesaler's role in the supply chain and underline his importance to the distribution process.

"Taking a leadership role means quantifying your value to the 'distribution channel, improving your level of value, and managing the flow of product and information," Prohammer says.

The technology revolution

Technology has been the driving force behind many of the changes in the industry over the last few decades, and it will continue to effect changes into the next century. And nothing in the technology revolution has changed the face of commerce more than the Internet.A wholesaler's competitors now have the ability to enter his territory by the use of Internet Web sites, online ordering and electronic funds transfer, all without building or buying even one branch, the DREF report says. Electronic commerce removes the geographic, technical and economic boundaries that have traditionally sheltered wholesalers from competition.

Wholesaler-distributor panelists say that the impact of electronic commerce on their businesses will triple by 2003. Their customers and vendors will drive the use of the Internet; they predict that two-thirds of their purchases will be made electronically.

But customer demands will affect wholesalers' strategy more than anything else. Tomorrow's customers will be more at ease with the Internet and more knowledgeable; as such, they will demand more information and self-service options.

"If the new value proposition largely lies not in products but in information, the race will be won by those who surround the products they sell with valuable information the customer needs about these products and others like them," the report states.

Of the wholesaler-distributors surveyed, 97 percent say e-commerce will allow them to collect, use and spread information. This could more fully integrate wholesalers into the channel and enhance their businesses through value-added services for customers and suppliers (see graph on page 23). Customer services that can be provided by e-commerce include 24-hour online order entry, customer service and technical support, electronic funds transfer, real-time inventory checking, the ability to access and compare a wide variety of information on products, and the ability to check the status of an order in transit and determine its time of arrival.

Value-added services for suppliers include highly accurate demand-forecasting information transmitted in real time, accurate and quantifiable information on customer preferences or problems, and marketing and technical information that can help the supplier develop new products.

More than 80 percent of the wholesalers surveyed see e-commerce as leading to strategic alliances with customers and suppliers, tightening the links in the supply chain.

Electronic commerce can present a threat to wholesalers, but it also can be used to strengthen their competitive positions in the channel. The report states that 60 percent of the wholesaler and supplier panelists agree that ecommerce will cause further consolidation in the industry; 40 percent of wholesaler panelists said that e-commerce would allow customers to bypass distributors.

However, while it may seem easier to "cut out the middleman," customers contacting manufacturers direct can add to their transaction costs, not lower them.

"One of the traditional strengths of the wholesaler-distributor from the customer's view has always been the wholesaler's relationship with many manufacturers," the report states.

Wholesalers should be more concerned about other business entities compiling the same information for the customer and bypassing the traditional distributor. About 62 percent of the wholesaler and manufacturer panelists say that e-commerce would lower barriers to new competitors entering the industry. With online ordering and next-day delivery, geographic barriers have virtually disappeared.

Strategic alliances

Access to new markets can also be acquired through strategic alliances, where a company retains its separate business identity but agrees to collaborate with others. Information, customers, market access, products and services, technologies, designs or other capabilities are shared to achieve greater results than if each business acted alone.Forming alliances requires determining the strategic goal, choosing a partner or partners, and deciding how to share responsibilities and manage revenues, expenses and profits so that both firms benefit - without merging the companies.

The report cites the alliance between W.W. Grainger and Perot Systems to illustrate a successful distributor/nondistributor partnership. The two companies are working together to develop an online order-entry system for Grainger's Web site (www.grainger. com). Through the alliance, Grainger gets access to technology without having to make a significant investment in software, and Perot Systems gains valuable experience in working with a broad industrial/MRO customer base and product lines. "Wholesaler-distributors that don't adopt alliances as one of their own tools may find themselves trying to meet the challenge posed by groups of more flexible, proactive competitors," the report states.

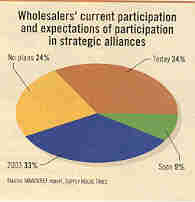

One-third of wholesalers surveyed for the report say they are engaged in strategic alliances; more than 70 percent expect to be involved by 2003 (see chart on page 23). Almost half agree that strategic alliances will dominate the wholesale distribution industry in the future.

Wholesalers surveyed expect 19 percent of their growth to come from total diversification - new products for new customers. Strategic alliances may lower the risk of total diversification by cutting costs, providing product/customer knowledge, reducing the time required to enter a new market with new products and decreasing financial risk.

While alliances can create opportunities for wholesalers, they can also create opportunities for new competitors by offering the means to enter a market without opening physical branches. Survey results indicate that wholesaler panelists are more concerned about traditional competition from wholesalers physically entering their markets. .

However, they see the importance of competition from other wholesalers entering their markets without establishing a physical presence doubling by 2003. The importance of competitors from other lines of trade allying with wholesalers in their markets could grow by a third in the next five years.

Strategic alliances can be a challenge to hold together over the long term. Barriers to success encountered in forming alliances include lack of control, friction between corporate cultures, conflict of interest, proprietary nature of product or function, cost, risk of failure, and the perception of a winner and loser.

But even alliances that eventually fail provide substantial benefits while they exist, the report says. In fact, successful alliances have often led to mergers and acquisitions.

Tightening the chain

Many of the best opportunities for supply-chain partners to improve their businesses involve removing redundant activities rather than trying to exact price concessions from each other. Both wholesaler and manufacturer panelists surveyed believe that redundancies can be reduced 2S percent. Inventory holding and selling costs are the leading sources of redundancy in the channel - accounting for about half of duplicated costs - while 38 percent are transactions and logistics costs."Wholesalers and their channel partners understand more than ever that the traditional 'push' channel model tends to raise inventory levels across the supply chain, increasing holding costs," the report states. "More trading partners have come to understand that a system oriented toward 'pulling' products through the channel based on customer demand is the most efficient model of distribution."

The need for a "pull" model based on actual demand information rather than on attempts to forecast demand is clear. Nearly all the supply-chain decisions made today are based on forecasts rather than on demand data, according to the report. The error rate of forecasting has been estimated as high as 40 percent, so changing the "push" model should enable supply-chain partners to significantly lower their inventory costs.

Increasing customer demands for speed and low cost, trading options made possible by the Internet, and escalating pressures on both customer and supplier executives for increased shareholder value have created a new business environment.

"Trading partners can no longer think of themselves as entirely separate entities," the report states. "They must be true partners working together to find or create the optimal supply chain."

What's a wholesaler to do?

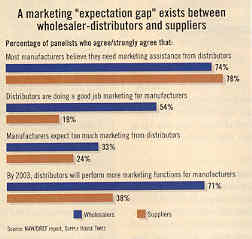

Survey panelists agree that suppliers need wholesalers' marketing assistance, but strongly disagree about how effective that assistance is - 54 percent of wholesalers say they are doing a good job, where only 19 percent of suppliers agree (see graph on page 24). While 71 percent of wholesalers see themselves as performing more marketing functions by 2003, only 38 percent of suppliers agree."This indicates that either a clear set of expectations has not been communicated or that the wholesaler-distributors' performance is better than suppliers perceive it to be," the report notes.

Three-quarters of suppliers surveyed don't understand the value of the marketing functions performed by wholesalers (see graph on page 26). Many suppliers view distributors' marketing function as a "necessary evil." It wholesalers don't demonstrate their value to their supply-chain partners, customer demands and vendors' desire to streamline the channel may force these partners to explore other ways of doing business - ones that don't involve a wholesaler.

"Wholesalers must not only ensure that the supply chain survives - or develop a new one better suited to the evolving environment - but they must also take a leadership role in this process to ensure that they are an essential link in the chain," the DREF report states.

A wholesaler can quantify his value by using activity-based management, a tool that helps a firm identify and measure the sources of costs related to the activities it performs every day, Rick Prohammer says. This can help wholesalers identify functions that add value and those that do not.

"Applied to the supply chain, activity-based management allows channel players to measure and evaluate their own costs, as well as those of their partners, identify and eliminate channel redundancies and assess the real value each member of the chain provides the customer," the report notes.

Providing the most value to the supply chain will result in more power for that channel partner to dictate terms, prices and other aspects of business transactions. Survey results indicate that suppliers see wholesalers adding more value in developing new product markets.

"To be successful in the future, wholesaler-distributors need to focus attention on developing downstream markets for their upstream supplychain partners," the report states. "They also need to involve their customers in growing and creating markets for the products the distributors hope to sell them."

It's a big world

Domestic manufacturing plants are now moving production offshore because of high labor costs in North America. Wholesalers who have been supplying maintenance and repair operations or original equipment manufacturer products to such manufacturers risk losing this business unless they extend their supply lines overseas.Half the wholesaler's suppliers are selling product outside North America; the number is expected to rise to two-third by 2003. Manufacturers see almost two to five times more opportunity in emerging global markets than their wholesaler-distributor partners. Lack of market knowledge seems to be wholesalers' biggest obstacle to entering foreign countries.

All panelists predict increased and more aggressive entry into these markets by 2003 - both in products supplied from and distributed to.

Rethink the supply chain

Using the four trends identified in the study to benefit an individual firm begins with the company taking stock of itself and identifying its core competencies."Developing a core competency, understanding the value it provides, and working to extend and leverage it is the only way to sustain value in the marketplace over the long term," the report states.

"A core competency is a bundling together of individual skills," Prohammer says. "It is a group of activities that a company does extremely well and sets it apart from the competition."

All core competencies meet the following criteria:

"When a company and its employees recognize the set of skills that constitutes a core competency, they can work together to actively build on it," the report states. "Employees can focus on how their roles contribute to further developing and leveraging it. Although a competitor may be able to copy individual skills, the culture a company develops over time by applying these skills to build a core competency is the head start competitors will not be able to replicate easily."

One aspect of accomplishing company unity is through knowledge management - the effective sharing of information throughout an organization. All departments and employees have access to the knowledge that creates value for the customer and increases the firm's bottom line.

Hiring qualified people and training them in the skills necessary to maintain a firm's core competencies is another aspect of building a strong company. Nearly 80 percent of the wholesalers surveyed say they are facing a shortage of qualified personnel, and all expect to double training expenditures by 2003.

The end result is making significant changes today to enjoy great success tomorrow. The report states, "Unless you maintain and develop these skills you will have neither core competencies nor competitive advantage, and you will run the risk of being swept away by the powerful forces that will continue to wash across the business world during the coming five years."

Sidebar: A great management tool

Charlie Banks, president and CEO of Ferguson Enterprises and chairman of the National Association of WholesalerDistributors, heartily endorses the most recent installment in the "Facing the Forces of Change" series of reports, put together by NAW's Distribution Research and Education Foundation and Arthur Andersen.Here are some of his comments regarding the report and its impact on the PHCP industry.