Year end is a time of reflection. For 2012, I’ve attempted to both inform and warn distributors about significant changes in B2B customer buying habits including use of e-commerce, use of handheld devices and growing acceptance of nontraditional distributors in the PHCP space.

This year’s blogs can be reviewed here . The gist of my writing concerns bundling services with products where the majority of services and products are commodities. When this bundling occurs, we typically find where 40% of the accounts deliver 140% of the operating profits of the wholesale firm. Looking at this another way, if the wholesaler employs 300, at any one time 180 folks are doing work for accounts that don’t add one nickel to the operating income.

Traditional wholesaling bundles services, labor, products and typically cost plus prices to deliver an average 2.5% return on sales. This bundled model worked well back in the day when information was difficult to get, delivery services were limited and the customer/seller interface had to be synchronized to be effective. Today, however, advanced logistics, better information flow due to the internet, e-commerce where selling and ordering can be asynchronous and detailed costing models that accurately estimate labor by transaction type all mean the bundled model is in trouble. Why?

To answer the question, I’ll use a fairly new entrant in the wholesale marketplace: Amazon. Amazon Supply is a recent entrant in the $120 billion MRO market in North America. Our review of its transaction costs using publicly available information and vs. Grainger finds that Amazon can process a standard stock transaction for some 60% to 70% less than Grainger. How? Amazon has no traditional branches, outside sales, inside sales and branch managers. In essence, its operating cost is low, typically much lower than most traditional distributors, and it passes along a fair portion of its cost advantage to the customer.

Amazon has been successful in hard goods retail markets in unseating traditional brick- and-mortar companies and it’s likely it will be successful in distribution markets — especially with commodity products that are easily stored and shipped. A recent study by the Boston Consulting group, on various commodities sold by distribution, finds that, more often than not, Amazon can beat traditional wholesaler prices by 25% on average. This pricing advantage is common among transactional distributors and has been cataloged by a number of studies.

Amazon is only one of a growing number of wholesalers we’ve termed as transactional. The transactional distributor is increasingly found in product vertical markets, and we recently found where an entity in the Upper Midwest scored a significant coup against a traditional PHCP bundled service distributor. We believe that there is significant room for transactional distributors or usage of transaction-based strategies in most traditional distribution circles.

Topics such as driving efficiency of solicitation efforts, streamlining and limiting services and products and taking cost savings to the customer will become more commonplace. Wholesalers who believe they can perpetuate a bundled, full-service model without accurate cost of service calculations and tough decisions on which services and products customers can do without aren’t dealing with reality where competitive operating structures are mandatory.

The problem with growth

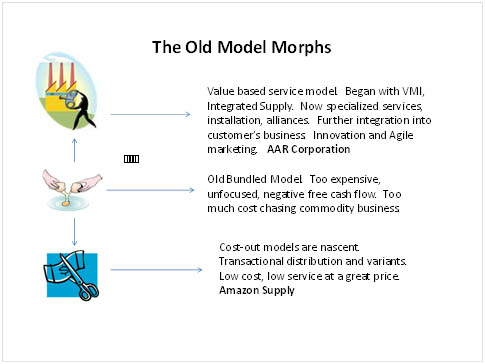

Increasingly, organic growth will come from two different platforms with a common thread. The bundled service model is literally being broken apart like an egg as depicted below.

Traditional bundled service wholesalers have two viable strategic choices in the post-recession economy. They can work to take cost out of the operating platform and become a low-cost producer, or they can go further into the value chain offering non-standard services and performing operations that their customers don’t want to do or can’t do efficiently. We believe most wholesalers will choose the value-added path but, to do so, they must have good measures and processes for new value streams.

Too often, we find where wholesalers create a value-added service from a function their customers don’t want to do or can’t do efficiently. The problem is that many of these efforts don’t have sufficient documentation, costing and an understanding if they make money. In short, whether the wholesaler chooses a cost-out strategy or a value-generation strategy for a supply chain business in an age of technological transparency, traditional financial accounting doesn’t give enough detail on which service investments contribute to operating profit.

In the post-recession economy, wholesalers will be pressed to better understand growth and define it in specific terms with specific action plans. Efficiencies will demand that growth efforts are measurable with specific labor costs and that they are well defined and within the wholesaler’s established capabilities. Simply acquiring other wholesalers or hiring new sellers is a losing proposition unless one has exacting plans, with good cost-to-serve metrics.

In a recent review of more than 100 public wholesale companies, the accounting lab at Georgia Tech found that these companies, even though they grew top line sales, were generating a negative free cash flow. In essence, they were funding new ventures with borrowings as their existing growth efforts didn’t generate sufficient returns to cover their capital costs. Too, growth will be seen more sufficiently more complex than it is today with many avenues to drive the profitability of the wholesale firm. To this end, we’re committed to researching the topic of top line growth and interested readers can go to our survey at: http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/N299TSB where respondents will get a free Executive Summary when the surveying is completed.

Strategy and growth efforts will be quite different in the post-recession economy. Wholesalers face challenges from new models of distribution as well as cost pressures from a much more transparent e-commerce world. New knowledge and preparation will go a long way in separating the successful from the not-so successful.

[i] Benfield, S. “Building Value: Driving Wholesaler Returns…,” page 87, Becon Publishing, 2012.

Recent Comments

AliPromoCodes

[No title]

Considering the fact that a lot of firms...

Thanks for the comment, Dinni!...

All I know is that companies need to...