"It's absolutely critical for wholesalers and manufacturers to squeeze costs out of two-step distribution to survive," says Jennifer Clark, distribution marketing manager for Johnson Controls' Controls Group.

"The old adage of distribution was that a commitment to buy was a commitment to sell," she explains. "For the last 30 years, manufacturers such as Johnson Controls have incentivized wholesalers with seasonal load-up, rebate and pricing programs that never really gave a true indication of demand in the marketplace. As a result, factory forecasting was based on means that weren't indicative of what items were really moving. Everything on the supply side was based on a push strategy."

This is also the conclusion of the National Association of Wholesaler-Distributors' Distribution Research and Education Foundation's report, "Facing the Forces of Change: Four Trends Reshaping Wholesale Distribution."

"Wholesalers and their channel partners understand more than ever that the traditional 'push' channel model tends to raise inventory levels across the supply chain, increasing holding costs," the report states. "More trading partners have come to understand that a system oriented toward 'pulling' products through the channel based on customer demand is the most efficient model of distribution."

To jump-start this initiative within the HVAC industry, Johnson Controls is teaming up with distributors such as Climatic Control Co., based in Milwaukee, to reduce inventory costs through supplier-assisted inventory replenishent (also known as vendor-managed inventory). These assisted inventory-replenishment processes use electronic data interchange and bar-code technology.

In an SAIR environment, a wholesaler's inventory is jointly managed with the vendor through electronic technology. As a result, proprietary information such as sales history is shared with the vendor. Trust becomes a key issue in the success of such a partnership. But the benefits to both parties outweigh any apprehension a distributor might feel divulging such information.

"The benefits for distributors are substantial," says Larry Rector, president of Climatic Control Co. "Lead times drop, customer service levels increase, forecasting accuracy is improved, inventory is reduced, transactional cost savings are realized and buyers are freed up to perform more proactive activities. There is better tracking of non-stock, seasonal and new items; fewer returns of overstock; and we shift from artificial reasons for ordering to demand-based reasons."

Manufacturers' benefits include timely and accurate channel usage, better forecasting that facilitates manufacturing efficiencies, improved customer service levels, reduced transactional costs and a stronger bond with the distributor.

Clark says that such electronic processes help wholesalers reduce inventory. Vendors can move product faster because they know what items are moving based on true demand. When engaged in SAIR, distributors will no longer receive inventory they don?t need. As a result, manufacturers have to rethink how to incentivize their distributors to buy product.

"We have to work much more proactively with our wholesaler customers to help pull the product through the marketplace," Clark says. "We've relied heavily on wholesalers in the last 30 years to do a lot of marketing for us. We are now partnering with them to help pull the product through."

Johnson Controls is also working with Amcon Controls (San Antonio) and is establishing SAIR relationships with G.W. Berkheimer Co. (Gary, Ind.), Gustave A. Larson Co. (Pewaukee, Wis.), and Refrigerative Supply (Burnaby, British Columbia).

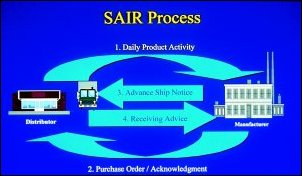

SAIR steps

NAW's DREF report states that redundancies in the supply chain could be reduced 25%. Inventory holding and selling costs are the leading sources of redundancy in the channel, accounting for about half the duplicated costs. And supplier-assisted inventory replenishment is an optimum way to accomplish this goal.Communication is the key to success of such a relationship. Kim Kendall, market analyst at Johnson Controls, says that, once a dialogue is opened between manufacturer and distributor (or distributor and contractor), the needs of both parties must be assessed, such as software or hardware updates. Service levels and turns must also be determined.

"Distributors want high turns but don't want to sacrifice service levels," Kendall explains. "We continually change the model until a balance is reached."

One time-consuming step is product data synchronization, or part number matching. UPC codes are loaded onto the distributor's system; the distributor must then verify that its part numbers match the manufacturer's.

The trust issue comes into play when a 24-month distributor sales history is collected. This is used to calculate demand curves, seasonality of products and trends. Distributors typically provide this data more than once during the process as the information becomes outdated as soon as it's provided to the manufacturer.

A stocking plan format is then selected and developed. Shipments are made on a schedule determined by the distributor: daily, weekly, monthly, by weight or by dollar amount. For most distributors, shipments will be once a week. Although the manufacturer may present a stocking plan to the customer, it is always reviewed and fine-tuned by the distributor.

"We want distributors to understand that they still have control over their own inventory," Kendall explains.

The EDI transaction sets are mapped at the same time the stocking plan is developed. Two EDI documents are required to begin the SAIR process -- a product activity document and a purchase order acknowledgement. Johnson Controls suggests two others -- an advance shipping notice and a receipt notice. The product activity form is sent electronically on a daily basis from the distributor and lets the vendor know how the inventory is fluctuating. This data is electronically compared to the stocking plan. The vendor sends the purchase order acknowledgement based on the nightly product activity document. The distributor uses the acknowledgment to open the order in its own system with its own purchase order number.

Once the stocking plan is final and the transaction sets are mapped, testing begins to ensure that both parties can receive the correct documents in their computer systems, as well as fine-tuning of the stocking plan. This may take one month to three months, Kendall says.

"Thoroughly testing the process is extremely important," she adds. "You want to make sure you test for all possible scenarios."

When the testing phase is complete and both parties are satisfied with the expected results, the process is moved into a production environment and supplier-assisted replenishment of the distributor's inventory begins.

Even though a stocking plan has been approved, it will change on a monthly basis based on such factors as sales and seasonality, Kendall explains. She electronically monitors Johnson Controls' SAIR partnerships daily by verifying that files are processing properly.

"It is not a stagnant process; we keep refining the turns and service levels based on the customer's goal," she says. "We're looking at ways to improve the relationship between manufacturer and distributor by opening the lines of communication and sharing information."

Management buy-in

To begin the SAIR process, senior management must make a firm commitment. "This is a business decision, not a technology decision," Clark says.Larry Rector opened a dialogue with Johnson Controls in 1998. "I asked them, 'Will you work with us on SAIR?'" he notes. "We spent much of 1998 preparing to do SAIR. We installed hardware and software and wrote programs to get us to that point."

He adds that any inventory-replenishment process should be part of a company's strategic business plan. Climatic added EDI and SAIR to its business plan in 1998; it deployed EDI in January 1998 and SAIR in August 1999."A couple years ago, this was totally new to us," says Don St. Martin, Climatic's vice president/operations. "It's important to have management commitment and it doesn't hurt to have a visionary who says, 'I believe we need to go down this path.' You have to take a lot of that on faith at first. Now it's just a way of doing business."

Because the project was too large to tackle all at once, Dave Smith, Climatic's management information systems director, split it into eight or nine smaller projects. This made the process more manageable.

"The hardest part is that technology changes so fast," he explains. "It gets cheaper or its functionality becomes more comprehensive. We were really shooting at a moving target. We'd get to a mid-point or some milestone and realize that we had to shift our focus a little bit. The basic objective didn't change, but the way we were getting there did."

"Climatic is constantly looking at the future and adjusting its goals," Kendall adds. "It does what needs to be done as technology and business changes. The company's management isn't afraid of the investment because of the final rewards."

It took Climatic about 10 months, 500-800 man-hours and many thousands of dollars to implement supplier-assisted inventory replenishment with Johnson. The company was not EDI-capable at the time; Rector says most of its hardware and software costs were EDI-based; no new hardware was needed for SAIR. As a result, the wholesaler learned quite a bit on the journey.

"You have to make mistakes along the way so that you can learn, and we never took our eye off the prize," St. Martin says. "We knew there was a tremendous learning curve that had to be overcome. But we realize that, with the next vendor that comes along, it could be a matter of three months or five months instead of 10. We have learned enough now that we can take that knowledge and turn it into a quick turnaround. That's part of the benefit -- taking the time up front, learning what you need to learn and using that information for your next partner."

Rector agrees. "Anyone going on with Johnson Controls today is going to have a much easier time in a much shorter period of time. I think we've helped them find the weaknesses in the system and showed them how to deal with distributors."

Kendall explains that a few data inconsistencies were found during the testing phase with Climatic, but they were overcome.

What Climatic has learned through this experience can be duplicated with other manufacturers. "Once you get your transactions set up and mapped, you're done," Clark explains. "You don't have to go back and redo it for each trading partner with whom you're doing business."

One size does not fit all

While Johnson Controls is committed to running 80% of its high-turn wholesale business on SAIR by year-end, Clark emphasizes that such a process is not for everyone."A one-size-fits-all approach with any channel is doomed to failure because not all customers in distribution are into the high-turn wholesale business," she says. "Many of them are working job by job, and lead times are unworkable. So we're carefully segmenting our customers in developing Internet-based, order-entry solutions for those accounts."There is the supply side and the sale side of the equation; wholesalers have to look at how automation is going to benefit their particular customer segments and also their purchasing habits. In some cases they'll be able to leverage both."

While a few companies are using SAIR with their contractors, Rector doesn't see that happening for his company in the near future.

"Today contractors are controlling their own inventory as they need it," he says. "We don't get large stock orders like we did at one time. It depends on whether the contractor wants to do it. Once we've done it with the manufacturer, we can move that technology to the contractor. I believe we're about two years from seeing that happen."

"We see SAIR as another business model for interfacing with a vendor or a customer," Smith adds. "The ability for distributors to automatically replenish contractors' inventory has obvious advantages. We have some contractor customers who may not be ready to leverage the technology yet but are ready to talk about the concept."

Rector is pleased with the progress his company has made with SAIR, as well as the way his management team implemented it. Climatic's management committed the funds and the time to research what upgrades or purchases needed to be made. They scheduled regular meetings to discuss the progress of the program and review results.

"It wasn't easy, but I don't know that we could have done it better," he says. "Whenever you're pioneers in something like this, you just jump in and do it. We never got discouraged. We had great people who were committed to the project and we got it done."

"There's no excuse to wait; the need for automation is now," Clark emphasizes. "We need to cut costs out of two-step distribution now. One of my biggest concerns is that customers are going to find another excuse to wait, and we can't. We have to move forward."